Across the various genres of photography, one question tends to link them all together: can a photograph objectively represent reality? While that remains to be seen, it was certainly a topic of interest for Kōji Taki, the Japanese critic and philosopher who founded the now infamous three-part photographic magazine series Provoke. Obsessed with the notion that photography in the 1950s and 1960s was driven by American and Japanese capitalist ideology, Taki strove to strip away these influences in an attempt to create what he considered to be ‘real’ documentary photography. Provoke, which was considered to be politically radical at the time of its release in the late 1960s, has received a lot of attention among academic scholars due to its timing and distinctive photographic style comprising rough, blurred, and out-of-focus (are-bure-boke) images, which have since become a trademark unique to Japanese photography.

While Taki’s goal was to ultimately criticize the capitalist state of Tokyo by producing aesthetically different images of ‘pure’ and ‘accidental’ reality in the form of ‘codeless’ photographic fragments, whether his goal was ever really accomplished remains unanswered. This essay aims to re-examine Taki’s concept and approach to photographic representation of reality, how it related to the social and political state of Tokyo at the time, and argues that the aesthetic qualities of Provoke failed to reform the discourse of documentary photography.

Before examining the aforementioned aspects, it is first important to note that photography has always had a unique situation in Japan. The first daguerreotype camera arrived in Japan in 1843, shortly after the photographic process was developed in France. However, due to Japan’s policy of maintaining closed borders, the camera was removed, and another didn’t arrive until five years later. It wasn’t until 1857 when the first known daguerreotype portrait was successfully created of Nariakira Shimazu, a daimyo (feudal lord) at the time. Moving into the Meiji period, Japan, now with open borders, was met with numerous foreign photographers who trained the first generation of Japanese photographers. It was then that photography began to take on a more prevalent role in society in the form of documentary photography used for a variety of events such as war, natural disasters, and the changing landscape of the country adopting Western industry, although what was presented and how so was heavily controlled by the ruling state. This also led to a genre of commodity photography known as “Yokohama photographs” (based from the port in Kanagawa Prefecture), which consisted of stereotypical images of Japan such as geisha, temples, and the like to be sold overseas, ultimately fetishizing the exoticism of this ‘newly-discovered’ land.[1]

The social function of photography in Japan grew, as well as belief in its credibility, which can be directly seen in its nomenclature. In English, the word photograph is derived from the Greek terminology light writing, however the Japanese word for photograph, shashin, translates as ‘truth copy’ or ‘reflecting the truth’, suggesting that a photograph is a direct copy of reality.[2] This mentality continued throughout the next century as photographers became known as shashinshi, or scholars of photography, with a social status on par with that of doctors and teachers—the character shi denoting mastery of a field.[3] Photography then took a new turn in the twentieth century in the form of fine art photography, when photographers began to experiment and add color via oil paint and the like to photographs in order to reinforce realism, which echoed it’s past status, but they later began incorporating manipulation techniques brought in from overseas.

Leading up to the Second World War, photographic genres in Japan began to expand including Pictorialism, Modernist avant-garde photography, realism, and propaganda. Photographers further defined in their genres, especially as Pictorialism grew more abstract and realist photographers looked to reach back to their shashinshi roots via documentary photography. However, the buildup of the Pacific War included employing these realism photographers to partake in propaganda materialization. The devastation left behind the Second World War not only affected the landscape and economy of Japan, but even caused the photographic mentality to shift into what was known as the Image Generation.[4] This new movement incorporated the practice of documentary photography, but with a more subjective viewpoint, arguing that imagery was also meant to be interpreted in addition to functioning as a record. Modelling themselves after the photo agency Magnum Photos, this group of photographers came to be known as Vivo in 1959. Their new approach included creative photographic techniques and unorthodox subject matter, such as disfigurement caused by the atomic bomb blasts. Although the group only existed for two years, its spirit resonated to the creation of the Provoke photographers a decade later.

The atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki signaled the end of World War II, as well as the end of Imperial Japan. Much of the country was left in ruins from the result of bombing and the economy was desecrated. Reconstructing the broken economy meant US forces and its Allies, known as the Supreme Command of Allied Powers (SCAP), would take over most of Japanese foreign and domestic issues such as demilitarizing its forces, dealing with its remaining colonies, and reshaping the government.[5] This cultural whiplash and military power castration had dramatic effects on Japan as it struggled with an abrupt loss of culture and identity. US military presence also brought about a sudden growth of capitalism and consumerism, forcing Japan into the new era while adopting its systems. This was further fueled by the buildup to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, just 19 years following the end of the War. In order to show the rest of the world its resilience, Tokyo began undergoing a total structural and cosmetic change, bringing about rapid urbanization. This included constructing new buildings, roads, ports, bridges, et cetera, most of which was designed by architects who incorporated organic, futuristic designs based on efficiency and graphics, known as the Metabolist movement, but largely focusing on the Tokyo Bay area. This rapid economic growth re-solidified postwar Japan as a world power, but it also had negative effects.

Tokyo’s new public image as a futuristic metropolis differed from that of how its residents saw the city, especially for those living on the outskirts. The Metabolist movement sought to “create the most rational balance among industry, capital, informational technology, and human life”. However, the rationality was that it never produced waste. Of course, this reality was completely neglected by the architectural Metabolists and it was “swept under the rug” and disposed of on the outskirts of Tokyo.[6] The aforementioned Provoke collective of photographers responded by documenting the harsh reality of this overflow of construction, people, and waste as well as the forgotten and overlooked back city alleys in images that highlighted the unseen side of postwar Japan while encompassing the collective mentality of society and those around it. They attempted to visually illustrate this feeling by employing the aesthetic techniques are-bure-boke mentioned in the introduction of this essay along with abruptly cutting off images by skewed cropping, embodying the concepts of sakka (friction, as per Provoke photographer Daidō Moriyama) and sakeme (rupture, as per Taki).

This new photographic technique, which seemed to employ ‘mishandling’ the camera to produce intentionally ‘bad’ photographs was meant to contrast the commercially clean environment of Tokyo being displayed. As Michiyo Hayashi writes in “Tracing the Graphic in Postwar Japanese Art”, “Provoke members addressed the formation of their own subjectivity-as-gaze in their practices. Broadly, the photographers tried to take advantage of the mechanical (nonhuman) nature of the camera as a parasitic ‘other’ within the gazing subject to produce an image that transgresses conscious authorial control but still somehow traces the opacity of the existential/material encounter between the photographer and the world. Thus, their images were often evocatively illegible.”[7] In short, the images created were derived more from chance and impulse than traditional photographic techniques such as concentrated composition. However, arriving at this aesthetic style is the result of the Provoke photographers’ collaboration and Taki’s own interpretation of the presence of governing forces in Japan, which were directly and indirectly controlling society.

In the first issue of Provoke, Taki explains his impression of the collective mentality of society and the need for an ultimate truth in “Memo – The Corruption of Knowledge”. He starts by claiming that chi (knowledge) moves in a ‘cyclical’ pattern as a result of information being recycled between the institutions and people, so ‘new’ knowledge that exists is not genuine, as the intellectuals who come up with this new knowledge are drawing it from the culture of hegemonic influence and not from within themselves. He suggests all the knowledge we have is fake. Furthermore, scientific discipline is controlled by the ideological institutions in power over society such as military, industry, and state capital rather than being that of a “holistic dimension”, the disciplines are independent of one another rather than being of a ‘oneness’. He often references the need for humans to overcome this by transcending toward a “nirvana” that exists beyond self-consciousness. Provoke’s aim is to focus on an area that extends “to a negative region below”, although just what this region is, is unclear. And although his essay doesn’t once mention photography, he is implying that in order to reveal this hidden truth, a type of ‘Buddhist photograph’ must be produced that captures an image beyond the world of self-knowledge and contains an ultimate truth without code. Although, for Taki, although this cannot be consciously achieved, meaning the use of the camera must take over in place of the thought-out or considered photograph. The act of taking a photo thus must mimic meditation in that it takes place in a subconscious state of mind as to create a photograph not rooted in or attached to any thought or idea whatsoever. If successfully followed, Taki’s theory would result in a photograph free of any ideological influences.[8] The biggest issue with Taki’s manifesto is that it lacks clarity and is full of jargon that was typical of radical leftists in Japan at the time. The other photographers’ essays in the issues of Provoke share a similar tone, such as Takahiko Okada’s argument of setsunai (frustrated emotions mixed with longing and admiration) as a driving force of capturing “obsessive images” driven by consciousness in his essay “Cannot see, aching with a setsunai feeling, and wanting to fly”.[9] His concepts, although deeply rooted in spirituality and well thought-out as they may be, fall short of practical application to the Provokecollective’s photographic practice.

However, to accomplish this, he utilized two main concepts: kankyō (environment) and his interpretation of Barthesian theory of a ‘codeless’ photograph. I will first begin by briefly explaining the paradox between the physical and perceived kankyō.

The word ‘environment’ when applied to photographic practice designates the area surrounding a place or thing and often the subject matter will interact with said environment, such as a teacher in a classroom (the teacher being the subject and the classroom being the environment). But this can be interpreted on a different, nonverbal level, such as suggesting the quality of the education system of a school and, by extension, superiority of intellect. Using the general structure of this analogy, Taki argues that every photograph ever taken has been done so in an environment in which ideological influences were present to some degree. Although not immediately apparent, every new photograph is “always an immediate sign” and the meaning is “programmed”, therefore subjectively controlled by the ruling capitalist state. Thus, the truth of reality of the world, as Philip Charrier explained in his essay “Taki Kōji, Provoke, and the Structuralist Turn in Japanese Image Theory, 1967–70”, “remains concealed beneath deceptive appearances and is inaccessible”, specifically as being run by this capitalist state exercising “hegemonic control over all forms of public material in Japan”.[10] But how can this be proven? Is it even possible to show physical evidence of an unseen ideological influence? These hegemonic messages, Taki insists, are known as the ‘codes’ transmitted via the photographs. This however, seems to have been an intentional misunderstanding of Barthes’ theory.

French philosopher Roland Barthes defined in his essay The Photographic Message from Image Music and Text the “course of reduction” that takes place during the transmission from the object itself to the physical photograph being merely of proportion, perspective, color, and the like—only visual perspective elements. However, it is not a transformation of the object being photographed.

In order to move from the reality to its photograph, it is in no way necessary to divide up this reality into units and to constitute these units as signs, substantially different from the object they communicate; there is no necessity to set up a relay, that is to say a code, between object and its image. Certainly the image is not the reality, but at least it is its perfect analogon and it is exactly this analogical perfection which, to common sense, defines as photograph. Thus can be seen the special status of the photographic image: it is a message without a code.[11]

Barthes argues that a photograph does not change the likeness of the thing being photographed. A rose or house pictured and later presented as a print is still the image of a rose or house; it does not take on the form of a signifier by coding ideas and emotions such as ‘love’ and ‘home’, respectively, but it is our minds and own ideology that does that. To draw such a message rooted in an image would mean to translate it verbally. It would be impossible for someone to describe the photograph as such even if they were able to derive such meanings because in doing so it would necessitate taking a denoted message from code, which only happens to be connected to language and text. Therefore, there is no need to provide any sort of relay in order to communicate a message between the object and the image beyond the function of the photograph itself because photographs are already messages without codes. However, in his efforts to document a specific type of reality, Taki then contradicts his own theory through the direct manipulation of imagery and not in a “neutral” or “objective” manner that would faithfully represent reality, as Barthes explains as the photographic paradox:

The photographic paradox can then be seen as the co-existence of two messages, the one without a code (the photographic analogue), the other with a code (the ‘art’, or the treatment, or the ‘writing’, or the rhetoric, of the photograph); structurally, the paradox is clearly not the collusion of a denoted message and a connoted message (which is the – probably inevitable – status of all the forms of mass communication), it is that here the connoted (or coded) message develops on the basis of a message without a code. This structural paradox coincides with an ethical paradox: when one wants to be ‘neutral’, ‘objective’, one strives to copy reality meticulously, as though the analogical were a factor of resistance against the investment of values…[12]

In fact, as the Provoke aesthetic was intentional and often a byproduct of experimentation and manipulation, it would be hypocritical to claim it as a document of true reality. Instead, the are-bure-boke look veiled reality because the aesthetic style was so heavily applied. Charrier explains Taki’s intentional misinterpretation of Barthes’ essay cuts against the grain of the original in two different ways. Rather than considering the semiotic duality of photographic images as a tentative theoretical basis for exploring how photographs communicate meaning, he treats it as a proven fact, describing it as the ‘destiny’ of photographs as if there were no other options in which to achieve his goal of capturing hidden realities free of ideology. The photographic act itself would essentially require complete mental detachment from the photographer and the camera, but the act of decision-making in pressing the shutter button would still be necessary.

And while Barthes treats the respective ‘codeless’ and ‘coded’ messages of the photograph “as equivalent theoretical concepts with no real-world social value”[13] as his description of the photographic connotation is “limited” by the difficulties in “providing a structural analysis”[14], Taki interprets this an absolute by adopting an “appraisive, polarizing viewpoint towards them”.[15] He regards the ‘photographic analogue’ as primary, natural, and pure, being superior because it doesn’t come from language and is straightforward rather than symbolic. Although the types of ‘real’ documentary photographs he praised were relatively standard images similar to that of what a photojournalist might take that exercise transparency between the scene and the photographer. These sorts of images documented a subject, such as a train passing on a railway, but also included the surrounding environment like houses and mountains as it provided “exact, objective evidence of some feature of the external world”.[16] And even though the codeless image possesses these virtues, it is displaced by its culturally entangled opposite, what is described as the art of the photograph. Taki’s ‘art’, however, soiled this purity. Thus, he concluded rather than replicating reality, the contemporary photograph is split off from reality.

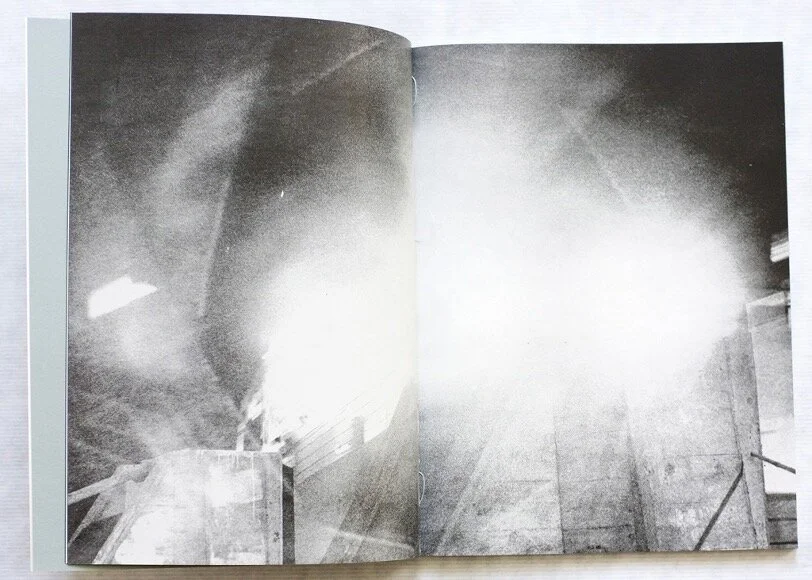

Why distort the photographs in are-bure-boke if they were already direct evidence of this non-reality? Does the are-bure-boke aesthetic really serve any purpose beyond suggesting itself as being something different from conventional photography at the time? But this wasn’t the only visual manipulation that took place. Gyewon Kim, in her article “Paper, Photography, and a Reflection on Urban Landscape in 1960s Japan”, explains at length that the collective not only experimented on the film itself during development, but also in the darkroom on the prints and with the paper on which the images were printed as they attempted to “reframe the discourse and practice of documentary photography”.[17] The resulting photographs, most of which the subject matter was only partially legible (example in figure 1) fall short of clearly showing what was documented from object to image. Therefore, claiming the camera as a neutral or nonhuman factor in documenting reality and then changing the appearance of the photographs themselves was detrimental in re-forging the practice of documenting the true nature and reality of the unseen ‘in between’ moments that were free of ideological influence.

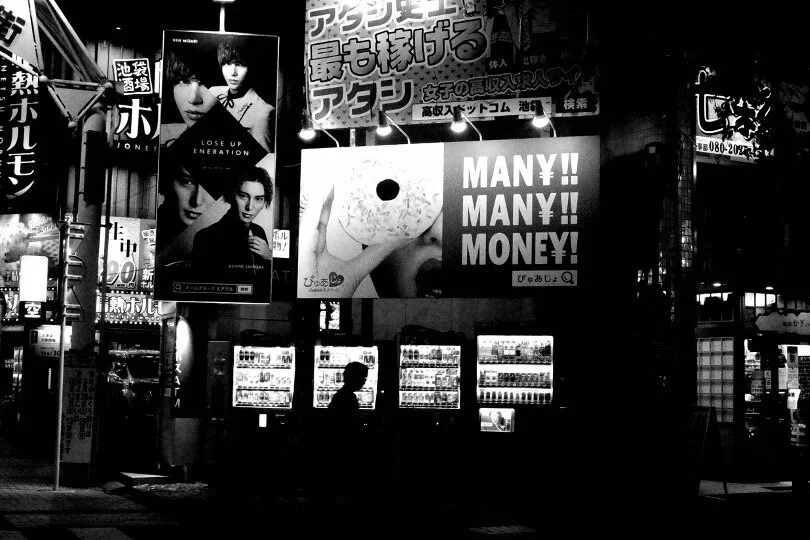

Therefore, given the aforementioned explanation, it is clear that Provoke failed in its goal to display photographs that transcended influence and reformed documentary photography. In fact, every photo ever taken is based from preconceptions, both individual and from influences. These are known as “photographic preconceptions” developed throughout the individual’s life that prioritizes importance on what should and shouldn’t be observed, and by extension, photographed.[18] The photographed subject matter is derivative of these visual priorities and to completely strip that away would be to completely erase everything in the mind and start with a fresh slate. Thus, no matter how much a camera is ‘mishandled’, or aesthetics are obscured, it is impossible to show a truly neutral reality. Provoke’saesthetics, however, have continued to ripple throughout the world of photography in ways Taki might not have foreseen. The camera company, Ricoh, which Moriyama was famous for using, markets its GR line of cameras that include the option of a high contrast monochromatic filter that can emulate the Provoke aesthetic (figure 2-5). Not only has Provoke been turned into a commodity for consumers, but Moriyama himself seems to indifferently apply the Provoke filter to the color digital images he takes while in his home studio as seen on a YouTube video posted by Tate.[19] In turn, this raises further questions if Provoke was genuine in its efforts to recreate documentary photography or if it has simply become a byproduct of the capitalist state Taki strove to escape.

Every photographer encounters the dilemma of how to frame a shot or even if they should take the photo. The truth is that objectivity in photography cannot exist. Even as a photographer myself with extensive training as a photojournalist and years of experience, I understand that objectivity is impossible. The individual thought of when and where the camera should be aimed and fired will always be based in personal opinion on what is photo-worthy and what is not, even when it’s the goal of the photographer to shed the ‘worth’ from the photograph. Even the impulsive swings utilized by the Provoke photographers aimed at letting the camera capture the ‘chance’ moment are still based in subjectivity and taken based on individual ideologies. Nonetheless, this doesn’t suggest that Provoke was a failure overall. As the series has become a valuable collectable among photographers around the world. The Provokecollectives’ efforts have inspired countless photographers around the world by creating an idea for photographers to grasp onto that they are free to shoot what they want and how they want to, rather than in accordance to social expectations and ideology of what photography should be. Ultimately, Provoke brought into question the very definition of photography and its role in society and how it can represent more than the transition of object photographed to an image as Barthes explained it, but to illustrate ideas.

Citations:

[1] Fraser, Photography and Japan, 11-13. [2] Ibid. [4] Fraser, “Photography and Japan,” 25. [5] “Occupation and Reconstruction.” [6] Chong, “New Avant – Garde,” 99. [7] Ibid. [8] Taki, Provoke, 14-19. [9] Taki, Provoke, 2. [10] Charrier, “Structuralist Turn,” 27. [11] Barthes, Image Music and Text, 17. [12] Barthes, Image Music and Text, 19. [13] Charrier, “Structuralist Turn,” 33. [14] Barthes, Image Music and Text, 16. [15] Charrier, “Structuralist Turn,” 33. [16] Charrier, “Structuralist Turn,” 37. [17] Kim, “Paper,” 231-232. [18] Doeffinger, Art of Seeing, 9. [19] Tate, “Artist Daido Moriyama.”

Figure 1. Untitled from Provoke 2, 1969 via Thomas Tallis School.

Figure 2. Skye Kühr, Untitled.

Figure 3. Skye Kühr, Untitled.

Figure 4. Skye Kühr, Untitled.